Sacramento Bee Misleads on Arena as Tax

/On his City Beat blog, Ryan Lillis, city hall reporter for the Sacramento Bee writes that opponents of a subsidy for the NBA Kings arena in the city are misleading voters when they say that it means higher taxes. In fact, the opponents are more right than Lillis.

It is a fundamental principle of public finance that any spending by a government that does not have its own currency must ultimately be paid for by individuals and firms — through taxes, fees, or exactions. As conservative economist Milton Friedman liked to say (in a phrase that liberal economists frequently quote), to spend is to tax.

So, too, with the proposed arena subsidy in Sacramento. The city's$346 million contribution to building the arena is a government commitment of public resources that must be repaid by the city's taxpayers. It's a tax of roughly $700 on every resident of the city.

How exactly that money will be collected is still an open question. Sacramento remains mired in the process that the New York bond analyst who writes online under the pseudonym Bond Girl describes thusly:

Officials then work with their friends in the banking community to craft some borderline-insane financing scheme that involves the city, or some puppet nonprofit established by the city, issuing a combination of tax-exempt and taxable bonds to pay for the new facility. Debt service will be paid from a combination of grossly exaggerated facility revenues and whatever other miscellaneous revenues the city manages to scrape together. (“Hey, how about parking revenues? Our parking garages will be packed once the city’s economy is rejuvenated by the presence of a professional sports team. The facility is practically paying for itself this way.”) Officials will then probably hire some economic (prostitute) consultant to reverse-engineer revenue projections that make the project seem feasible. Maybe the city decides to back the bonds directly.

Whatever "borderline-insane financing scheme" ultimately emerges, one fact will remain: any public resources devoted to the arena could otherwise be used to pay for other city services like police, fire, parks, culture, and libraries, or to reduce taxes. To spend is to tax.

What Lillis neglects to tell us is that the signature gatherer he ignorantly brands as "misleading" is doing no more than paraphrasing what the Bee's own columnist, Dan Walters, has suggested: that the higher Measure U sales tax enacted in 2012 and due to expire in 2019 will be used and extended to pick up the arena bill.

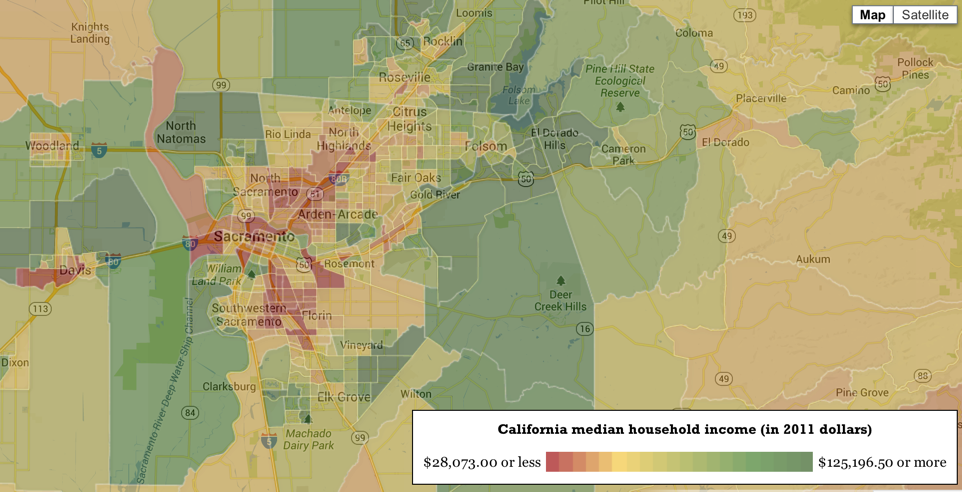

Supporters of the arena subsidy understandably don't like to talk about it as a tax. Mayor Kevin Johnson is demanding that his city, home to the poorest residents in the region, carry the entire burden for a facility that caters predominately to higher-income people. (This may explain why the strongest supporters of the subsidy live outside the city; it's easier to love a tax you don't have to pay.)

And it's even harder to talk about the arena as a tax when your city already has the highest taxes in the region. Only Galt has a sales tax as high as that in Sacramento (8.5%). The city's utility user tax rates (7.0% and 7.5%) are triple those in other parts of the region. These taxes are both highly regressive, hitting the essentials of life—heating, cooling, clothing—that make up a high percentage of the budgets of the poor. The city that's home to many of the region's poor hammers them hardest.

Vigilant and useful journalists would be explaining this to the region. Instead, as in so much of the Bee's cheerleading coverage of the arena subsidy, Lillis brands as "misleading" the very citizens who are raising the right questions about who benefits from the giveaway and what it might mean for the future of a financially and economically troubled city. He owes them an apology, and the Bee owes its customers and city better reporting and analysis.