Scoopy Plays the Race Card

/I didn't think it possible for the Sacramento Bee to come up with a less persuasive case for Kevin Johnson's strong-mayor push than the one I took apart in the last post. But then this editorial got dropped on my porch this morning.

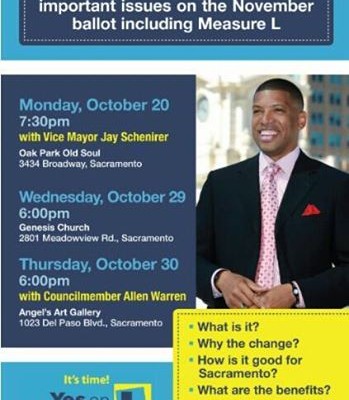

The Bee repeats its plaintive cry: "Sacramento must separate Measure L from the mayor." As I previously noted, this is impossible. Kevin Johnson and the strong-mayor push are like conjoined twins who share one heart. They are inseparable. One can't live without the other. Even Kevin Johnson thinks so. Look at Measure L's own campaign materials.

It's all about Boss Johnson, and always has been. When the Bee tries to suggest otherwise, it's pissing into the wind.

From there the editorial goes downhill.

When we subscribe to a newspaper, one of the things we expect for our money is journalism that provides some context and depth to make sense of the flood of events, information, and spin that come at us every day. The Bee can no longer seem to do that.

It attributes the opposition to Measure L to "some in the old guard," people who never fully accepted Kevin Johnson and who "would prefer to keep a political system that worked when the city was smaller." Leave aside for a moment the obvious fact that the council-city manager system continues to work pretty well in big cities that are doing much better than Sacramento, a fact that an intellectually honest editorial would have to acknowledge. The big lie here is that somehow it's the "old guard" behind the opposition to Measure L.

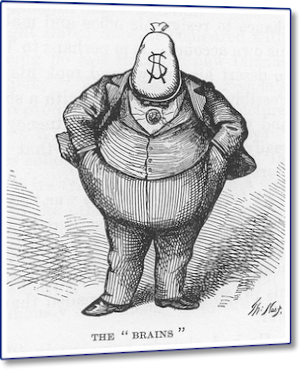

That's nonsense. There's nobody more "old guard" than the people supporting the Measure L push: Angelo Tsakopoulos, the Friedman family, the Chamber of Commerce, the cops and firefighters. On the other hand, the opposition campaign is headed by rookie Councilmember Steve Hansen, who, at age 34, is hardly a member of the old guard. The fact of the matter is that there are young and old, both people who voted for Johnson and people who voted against, on both sides of the strong-mayor debate. When you don't have any evidence to support your position but aren't honest enough to say so, tarring your opponents becomes a temptation.

And that's when the editorial spirals down into the muck: "It does make you wonder whether some of these personal attacks on Johnson, Sacramento’s first black mayor, have something to do with race."

That's an astonishing thing to read in what purports to be a professionally edited metropolitan newspaper. Not because there aren't people who will vote against Measure L because the mayor is African-American; this is, after all, the United States. But because it maligns a wide swath of the community with no evidence to support the claim. A leading foe of the strong-mayor measure was the late Grantland Johnson, the city's most prominent black politician for three decades as council member and county supervisor, who signed the opposition ballot argument before he died earlier this year. It's also signed by Bonnie Pannell, another long-time African-American member of the council. Does the Bee believe their opposition has "something to do with race?" Does it believe that they would have associated themselves with the opposition if it did have "something to do with race?"

It's an axiom of Internet debate that the first person to invoke Nazism loses the argument. There's an even older newspaper corollary: An editorial page that "wonders" in print, without supporting evidence, whether a large and active part of its city and its readership is racist has not only lost the argument; it has lost its moral compass.