Strong Mayor? Why? Part 2

/In the last post, I disposed of the claim that switching Sacramento to a strong-mayor system would make city government more efficient. Let’s look now at the oligarchs’ second argument: that strong-mayor cities are more responsive and accountable to voters.

Unlike the first, this second argument is at least plausible. The wealthy businessmen who promoted the city-manager system a century ago were no friends of the urban masses. They argued that “good government,” as they defined it, was more important than self-government. City managers were to be freed to run cities according to dictates of science and efficiency and to operate outside of “politics,” the realm where responsiveness and accountability reside. The possibility that city-manager governments can ignore the wishes of their voters is encoded in that system’s DNA.

In practice, though, scholars haven’t found any evidence that one form of city government is more responsive or accountable to voters than another.

The most recent and sophisticated of these studies, by political scientists Chris Tausanovitch of UCLA and Christopher Warshaw of MIT, compares the ideological leanings of residents of 51 large cities with the policies adopted by their local leaders. They find liberal cities get more liberal policies and conservative cities get more conservative policies, regardless of the form of city government.

“In contrast to the expectations of reformers, we find that no institution seems to consistently improve responsiveness…,” they report. “City manager systems, designed to be more professional and less political, appear to be just as responsive to public opinion as their mayoral counterparts. Given the same set of public policy preferences, a city with a mayor looks almost exactly the same as a city with a city manager for most policy outcomes.”

Jessica Trounstine, the UC Merced political scientist, provides a similar perspective in her fine recent book, which looks at occasions when powerful and unresponsive coalitions were able to establish political monopolies in city governments. These unaccountable monopolies arose, she finds, in both strong-mayor and city-manager governments, differing only in the tactics they used.

The verdict? Judged as to whether a strong-mayor system provides more responsive and accountable city government than Sacramento’s current city manager system, the oligarchs’ case once again fails.

So why do the wealthy and powerful pouring so much money into the strong-mayor campaign continue to argue that the reform will make the city more efficient and responsive even when decades of scholarly research and experience show that it won’t?

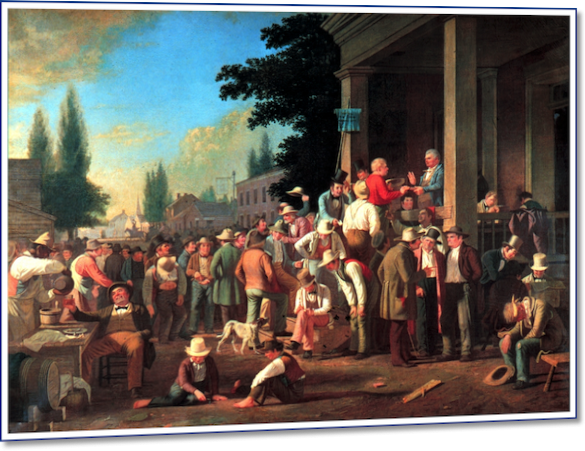

Because what alternative do they have? Words like “efficient” and “accountable” are talismans in any debate over city government organization. If the oligarchs and Kevin Johnson didn’t claim those magic words and try to own them, their opponents would. It was for the same reason that the wealthy civic reformers of a century ago so often invoked their devotion to “the people” even as they busily went about suppressing voter participation and shifting city power away from voters and toward unelected professional administrators.

Having taken the would-be reformers’ rhetoric seriously enough to assess it and find it empty of substance, I’ll offer, in the next post, a hypothesis about the real meaning of the push for strong-mayor system.